As I began researching my latest book Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus, I realized that a basic question was a puzzle to me. How was the Bible read and preached in the first-century synagogue?

Every Sabbath for thousands of years, the synagogue service has focused on the reading of the Torah and the Prophets. This is mentioned in Acts 13:15. For dozens of centuries, the tradition has been to read through the Torah over a year, and to read a corresponding passage from the Prophets.

Is that what Jesus would have known? Yes and no. The Torah and Prophets were read each week, but the current liturgy was developed around 400 years later in synagogues in Babylon. Before that, an older, earlier tradition existed that was largely unknown to scholars until about a century ago.

The Triennial Reading Tradition

In the earliest period, the readings were spread over approximately three and a half years, differing slightly from town to town. Also, synagogues did not have a single leader who preached every week, like a rabbi or pastor does today.

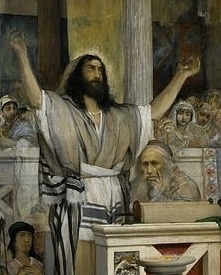

Instead, one adult member of the congregation (or an educated visitor) would be invited to read the Torah portion. He would then choose a prophetic passage that fit the Torah reading, and would give a brief meditation on how the passages relate to each other. The prophetic reading was called the haftarah (HAHF-tah-rah), meaning “completion.”

This is what we see Jesus doing in Luke 4:17-18 when stands up in his hometown synagogue and reads from the Isaiah scroll. Most likely Jesus also had read the Torah portion, but Luke doesn’t mention it.

Focused on God’s Messianic Redemption

The discovery of the “triennial” tradition of reading the Torah was a surprise to Jewish scholars, who had been following an annual liturgy for 1500 years. It had been developed by rabbis in Babylon, while the older triennial tradition persisted in Israel, Egypt and northern Africa until the annual cycle became universal around 1100 AD.

In looking at the Torah and Haftarah readings, scholars saw some similarities between the two traditions, but also some key differences. The later Torah readings were clearly derived from the early tradition, but the Haftarah texts were completely different.

In the annual tradition, the preassigned readings from the Prophets usually focused on Israel’s past, connecting the events in the Torah with other historical accounts in Scripture.

In the earlier tradition, however, the readings focused on the future, on God’s promised messianic reign over the world. Every week, synagogues were listening to God’s word and asking how God’s redemptive plans would come to pass.

This should fascinate Christians, as well as the fact that the book of Isaiah was a favorite source of readings, especially Isaiah 40-66. These same chapters are prominent in Jesus’ teachings, as well as in Paul’s writing. (Notice that Jesus’ reading in Luke 4 was Isaiah 61:1-2 and Isaiah 58:6.) Isaiah is not common in the modern lectionary.

In the First Century

Scholars believe that the triennial reading tradition was still developing in the first century. In that period, it was actually up to the weekly speaker to chose the prophetic passage. Doing so, however, required a Google-like knowledge of the biblical text. Often the passage began by overlapping with the first few words of the Torah portion (a “gezerah sheva“). Then it would expand on the Torah in some profound way and end with a promise of God’s coming redemption.

What did this sound like? When Genesis 1 was read, the traditional Haftarah was Isaiah 65:17-25:

“See, I will create new heavens and a new earth.

The former things will not be remembered,

nor will they come to mind…

The wolf and the lamb will feed together,

and the lion will eat straw like the ox,

and dust will be the serpent’s food.

They will neither harm nor destroy

on all my holy mountain,”

says the Lord. (Isaiah 65:17, 25)

Notice how this passage begins by echoing the words of Genesis 1:1, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” and then ends with a wonderful promise of the New Creation. As the ancient readers meditated on the beginning of history, they would think ahead to God’s vision of a redeemed earth.

You can see many sermons in early Jewish commentaries (midrashim) that are built this way, by relating Torah readings to prophetic passages and then preaching about the implications.

Over the centuries, the prophetic readings became more and more standardized. You can imagine that for any Torah reading, only a limited number of prophetic texts would be appropriate. Certain passages became “magnetized” to specific Torah readings, having been preached together year after year. Centuries later, these were collected into reading lists.

What is fascinating is how some classic “magnetized readings” come up even in the New Testament. For instance, a traditional Haftarah for Genesis 16, the story of Sarah and Hagar, is Isaiah 54:1-10, God’s eschatological promise of bring joy to the childless:

“Sing, barren woman,

you who never bore a child;

burst into song, shout for joy,

you who were never in labor;

because more are the children of the desolate woman

than of her who has a husband,”

says the Lord. Isaiah 54:1

In Galatians 4, we find Paul using Sarah and Hagar’s story in his discussion, and then pulling in Isaiah 54 at the end. It is thought that he did this because these passages were already linked in people’s minds, having been read together regularly in the synagogue.

We also see this in 2 Corinthians 3:6-18, which echoes two other “magnetized” texts, Exodus 34:27-35 and Jeremiah 31:32-39. Exodus 34 describes Moses breaking the tablets when he finds the Israelites sinning, and then receiving a new set of tablets. Jeremiah 31 is God’s promise to make a new covenant for the forgiveness of sin.

Christians should be fascinated that a prominent theme in early synagogues was the fulfillment of God’s prophetic promises. It fits perfectly with Jesus’ ministry of preaching from town to town about the coming of God’s redemptive Kingdom.

For more about this tradition, see chapter 10, “Moses and the Prophets Have Spoken” in my new book, Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus. If you want to study further, see below.

~~~~~

Audio Discussions Online

For the past couple years, I’ve been involved with the Bible study at Narkis Church in Jerusalem that is going through the triennial readings and posting their discussions online. The leaders are quite knowledgeable about both the Tanakh and the Jewish context of the New Testament, and add many insights from Hebrew and Greek. The group actually got interested in the triennial readings after I gave an overview in 2015, “The Haftarah of the Kingdom,” which is at this link. They’ve since been recording their discussions online and I’ve been participating at a distance. (Note: recordings are informal and rough at times.)

In the summer of 2017 I gave two more talks when I was in Jerusalem. We had really good discussions both mornings, if you have time to listen:

On July 8, I repeated my overview and we discussed what we had been discovering.

On July 15, I led a study of Leviticus 17 and Isaiah 66, and noted how reading those texts together sheds light on Jesus’ words in the Beatitudes.

~~~~~

For those who want to study further…

I have attached a pdf document with the triennial reading list from one my main scholarly references, “Reading of the Bible in the Ancient Synagogue” by Charles Perrot, p 137-159, in Mikra (Compendia Rerum Iudiacarum ad Novum Testamentum), (Van Gorcum) 1988. This is a consensus list of readings from manuscripts from the 3rd to 7th century. It’s one of the best scholarly references available.

A couple caveats for readers:

Caveat 1. Be wary of what you find online.

Christians are obviously curious to study more, but not a lot of material is online from scholarly sources. What you find is often speculative and outdated. This is because some of the first studies that were published were full of theories that went well beyond the data. As more texts surfaced, these theories became more and more obviously unsupportable. Scholars started to avoid the topic, but laypeople became enamored with early speculation and have put it all online.

This is why the list of readings that I’m sharing comes directly from a scholarly source, so that you can see where it is partial or incomplete. I haven’t tried to construct a “Messianic triennial lectionary,” like what you’ll find if you start googling. No such thing exists from the first century. What has been found is lists of readings from several centuries later, as well as clues from ancient synagogue hymns and early rabbinic sermons. We have suggestive evidence of what was read in early synagogues, but we do not have explicit data.

Even knowing this, I’ve found that study of the ancient triennial reading list is very rich, because it shows the exegetical connections that early Jewish readers were making as they read their Scriptures. I often find that they help me understand the thinking of the New Testament writers, and even suggest insights into Jesus’ preaching. (See chapter 10 in Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus for more.)

Caveat 2. Overt messianic references have likely been removed.

You might be curious about looking up a prophecy about Jesus, like Isaiah 7:14, about a virgin bearing a son, or Micah 5:2, about a ruler being born in Bethlehem. Unfortunately, scholars believe that passages with clear Christian claims were deliberately excluded from synagogue liturgies. (See the article “What Happened to Jesus’ Haftarah?” from Ha’Aretz – Aug 12, 2005). Even triennial readings (the lists of which date from later centuries) appear to be somewhat sanitized.

This is a good lesson to Christians exploring their Jewish heritage. Many are shocked by how the church has lost so much rich knowledge because of its hostility toward Judaism over the centuries. But Judaism did not take this lying down. As Christians were separating Jesus from his Jewish roots, Jews were separating from him too. When Christians read Jewish sources about Jesus, they should not expect their opinions to be neutral.

References

Steven Di Mattei, “Paul’s Allegory of the Two Covenants (Gal. 4.21–31) in Light of First-Century Hellenistic Rhetoric and Jewish Hermeneutics,” in New Testament Studies 52 (November 2006): 102–22.

Michael Fishbane, JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot (New York: Jewish Publication Society, 2002), xix–xxxii.

Charles Perrot, “The Reading of the Bible in the Ancient Synagogue,” Mikra, ed. Martin Mulder (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988), 137–59.

Vicki says

This is fascinating! You explain it so well. Thank you for taking the time to lay out the information step by step. I’m especially looking forward to hearing more about the connection between Lev. 17 and Isa. 66. I’ve always thought I’m not really getting a full understanding of the Beatitudes. Thanks Lois!

Merilyn Copland says

Thank you for your very clear explanation. This is so needed in a time where people read for a “quick blessing” within five minutes and are unaware that there is so much more to think about and respond to.

Larry Geiger says

In the .pdf what does the “Seder” column mean? The numbers go from 1 to 158. Is each one a week? So 52 X 3 = 156? Three year actually have 158 weeks? Thank you.

Lois Tverberg says

The “seder” column simply gives a number to each Torah reading according to the consensus of the traditions that have been found. In the older tradition, each Torah reading was called a “seder” (pl. sedarim), whereas in the annual tradition, it is called a “parashah” or “parsha” (pl. parashot). The reading from the Prophets is called the “haftarah” in both traditions.

In Hebrew the word “seder” means “order,” and refers to the order of readings. At Passover, they celebrate a “Seder,” which refers to the observance of readings and traditional foods, which follows a set order too.

Regarding your second question, about the numbering of readings that goes to 158. As I said in the article, the amount of time it took to complete the Torah was around three and a half years, and varied slightly from town to town. Some reading lists had as few as 140 readings, some up to 170 readings. What is in the pdf is a consensus of the most common readings. A few places you’ll see numbers like “10a” or “36a” because some lists started and stopped at slightly different points in the text.

When this reading tradition was first discovered, they called it “triennial” because they thought it was intended to take exactly three years. No one thinks this is true now, because the weekly readings would pause for the observance of special Sabbaths and feast days. Some now call it a “semi-septennial cycle” because it was completed about twice every seven years, but there is enough variance that most scholars don’t assume that the aim was to finish in an exact time period. The need to synchronize readings across synagogues and finish at an exact time were both novel characteristics of the annual liturgy.

Tommy Keefer says

I am curious since Yeshua fulfilled moedim. Could Isaiah 1 fulfilled in their eyes been on Yom Kippur as they tried to push Yeshua over the cliff like the goat. I realize this is speculative. Please comment , Tommy Keefer on Kauai. patriciaandtomkeefer@gmail.com

Lois Tverberg says

Tommy, I disagree with your first line. To fulfill the moedim (feasts) does not mean to check them off to bring them to and end. This is the same problem as with “fulfilling the Torah.” I’ve written a 3-part article that begins at this link:

What Fulfill the Law Meant in its Jewish Context

Lois Tverberg says

I’ve been asked a couple times now about the annual synagogue tradition being instituted in Babylon around 400 AD. Was I talking something that happened in Babylon in 400 BC rather than AD?

No. A large community of Jews remained in Babylon after the return from the exile. About four centuries after the dawn of the Christian era, the Babylonian community became the dominant center of Judaism. The Babylonian Talmud, one of the most influential collections of rabbinic thought was put into writing there around the same time as the annual liturgy was developed.

(A PS about why I use “AD” rather than “CE” – because I aim to communicate with a traditional Christian audience. For more about this, as well as why I use “Jesus” instead of a more Hebraic form of his name, see this link.)

Doug Ward says

Great post! This is of special interest to us at Church of the Messiah, where we are in the second year of a 3 1/2 year cycle and enjoying the journey.

Pastor Ron Murhon, Sr. says

Greetings Lois, Peace be with you your household and staff. I am reading your newest book, and i will put the world out to my flock and anyone else who is interested. I must say: “I believe your best and greatest work was and still is (in my eyes) Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus. Be safe my friend, and be blessed. Shalom Ahava, Pastor Ron>

Warren Cederholm says

Thank you for this great insight into Judaic practices at the time of Jesus. I have a learned Jewish friend who I often turn to when I have questions about today’s Judaism, but she was quite surprised to learn of the beginnings of the “lectionary” at and before the time of Jesus. It has truly helped with my understanding of the Lucan text for the 3rd Sunday of Epiphany, Luke 4:14-21.

Was rabbi (rav) an earned title after completing some “test?” Or was it an honorary title?

Can’t wait to read some of your other articles. I had preached for nearly 20 years and then took an assignment for 20 more years in which I seldom had to preach. Now in retirement, I’m serving a small local, but very well educated church. I forgot how much I missed sermon prep and stumbling across interesting facts. Thanks for your help this week, I will be looking for your work for further study.

Lois Tverberg says

Thanks. I”m glad if they have blessed you.

Regarding the use of title “rabbi/rav,” see my article, Can We Call Jesus “Rabbi“?

Dr MJ Eilers says

Good day to you. Do we know the Jewish year, month and day when Jesus preached in the Synagogue of Nazareth after reading the Haftarah, Isaiah 61:1 and 2.? Was that Scripture prescribed or did Jesus deliberately read that passage?

G-d bless

Susan Phillips says

I am so grateful to stumble across your site and to know of your books. I am quite interested in Dr. MJ Eilers’ question from Feb. 8 concerning the text from Isaiah that Jesus read in Luke 4, and I, too, would like to know if that particular passage had been prescribed as part of the Torah reading for that service. What piqued by curiosity was this part of verse 20: “and the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed upon Him.” I quickly thought that perhaps Jesus had read a section out of sequence, and as a result, the congregation was surprised and waiting expectantly to see what He would say next. At any rate, I became curious about the liturgy of the time, and I look forward to reading your books now and to seeing other comments posted here. Thank you!

Glenys Chew says

Thank you for sharing this insight 🙂

I’m new to your books, and am going to create a personal form of haftarah by seeing what Scriptures I associate with my daily Bible reading. Eg, I’m was in the Lamentation of Jeremiah , and immediately thought of Mt Ebal (Deuteronomy 27,28 and Joshua 8), as well as several others. I’ve started a table to record these personal cross-references.

But they opened a question for me, which I may not have noticed the ready answer to in your information.

It seems to me that much of the ancient Haftarah would have had to based on the revealed Scriptures (pardon my ignorance as I learn: this is the Torah and the Nevi’im?) according to the date of their composition?

That is, a Haftarah from Asa’s time wouldn’t have as many readings as one from Zedekiah’s time, or post Exile, for example, simply because the prophets were still in the process of being sent?

I wondered if this gives any insight into the unfolding revelation of the Father’s promises as seen in each time period/era, and which ones were most treasured by the ancient scholars and Israelites generally?

Lois Tverberg says

Synagogues did not exist before the return from exile. We don’t have much data on how they arose over that time and what the practices were before the first century AD. In fact, Luke 4 records the oldest tradition of the Torah and Prophets being read in the synagogue. Jewish scholars were happy to see this because it confirmed the antiquity of their traditions.

Greg Killian says

I have been studying the triennial cycle, with my Rabbi, for more than 30 years.

Steve Kuban says

Thank you Lois for your very informative writing, it’s my first time to read your words and I’m very excited to read more of what YHVH has revealed to you through the years of your diligent studies for Him. Thank you for sharing with us.

Lois Tverberg says

Steve, great to hear you’ve been blessed. Thanks. Lois