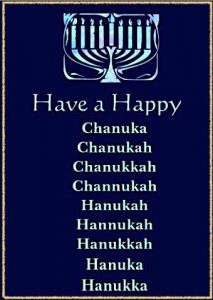

Hanukkah is being celebrated right now, and one of the first questions people ask is why there are so many different spellings. Which is the real, correct spelling?

Hanukkah is being celebrated right now, and one of the first questions people ask is why there are so many different spellings. Which is the real, correct spelling?

If you want to know the truth, here it is:

I know, I know, seeing a Hebrew word is unsatisfying. ּּBut the true, “correct” spelling of the word is in Hebrew, and it’s het-nun-vav-kaf-heh.

That’s actually the answer to why there are so many spellings. All the English variants are just approximations of a word which is actually in Hebrew.

Foreign words often don’t have “correct” English spellings. Some of the spellings of חנוכה are more common than others, of course. Hanukkah is the most common, followed by Chanukah.

Multiple Spellings of Hebrew Words

Rendering the sounds of one language directly into another is called transliteration. This is not always easy, because often the sounds of one language aren’t produced in another. Sometimes there are simply no characters to spell the sounds that you need to say.

The first letter of חנוכה sounds kind of like a roughened “h,” so some spellings start with “ch” and some with “h.” Since English doesn’t have this exact sound, we just choose a close equivalent.

You might have noticed that with hallelujah has many variations in spelling too. A similar thing happens with a lot of Hebrew words. Sometimes you see chutzpah, sometimes chutspa or hutzpah or hutzpa. You find both Torah and Tora used, and shema, shma, and sh’ma. That’s because the real word is in Hebrew, and the English word is just an approximation.

You might have noticed that with hallelujah has many variations in spelling too. A similar thing happens with a lot of Hebrew words. Sometimes you see chutzpah, sometimes chutspa or hutzpah or hutzpa. You find both Torah and Tora used, and shema, shma, and sh’ma. That’s because the real word is in Hebrew, and the English word is just an approximation.

Sometimes, a word that was once foreign actually enters the language and becomes English. The word “sabbath” comes from Hebrew but we’ve had it for so long that it really is an English word. If you’re transliterating the Hebrew word, however, you would write “shabbat.”

Assuming that there should be one correct, authoritative spelling of a word is a relatively late development in English, actually. Spelling became standardized only after the printing press was invented in the 1400s. Shakespeare once wrote a letter which included his name in four places, and every single time he spelled it a different way.

Road Signs Too

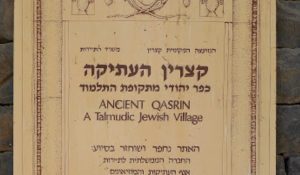

If you drive around Israel, you’ll notice a related phenomenon on road signs. Take a look at these signs that point the way to a historic village near the Sea of Galilee.

If you drive around Israel, you’ll notice a related phenomenon on road signs. Take a look at these signs that point the way to a historic village near the Sea of Galilee.

In one the name is spelled “Katsrin” and another its “Qazrin.” You’ll also see the name spelled “Katzrin,” “Kazrin” and “Qasrin.” Even government signs will have variations.

Notice, however, that in Hebrew, the name is always spelled the same way:

Why? Because of the assumption that the English spelling of the town’s name isn’t terribly important. It is just a rough approximation of a Hebrew word. If you want to spell the name correctly, spell it in Hebrew.

Why? Because of the assumption that the English spelling of the town’s name isn’t terribly important. It is just a rough approximation of a Hebrew word. If you want to spell the name correctly, spell it in Hebrew.

Learning about the Name of God

For thousands years, a Jewish tradition has been for synagogues to store worn out Bibles or prayer books until they can be reverently buried in a cemetery, so that God’s name is never willfully destroyed.(1)

I once asked a rabbi if I could contribute some books that had been damaged in a flood, and his answer surprised me. Only the ones that contained the name of God in Hebrew, (yod-heh-vav-heh) needed to go there, not the ones in English.

Why? Because the name of God is not truly written in any other language besides Hebrew. The written word “Yahweh” is only an approximation, not the real thing.(2)

I found this fascinating, and it challenged my monolingual assumption that English was the measure of all human speech. It was hard for me to even imagine words existing that weren’t written in Roman characters.

When I first encountered Hebrew, I crassly quipped that all of the letters looked liked little boxes, except for the one that looks like a crown (ש). It stretched my imagination that those cryptic little boxes actually make sounds, and even that they are required to spell a word as important as the name of God!

~~~~~~

(1) Israel was commanded to blot out the names of foreign gods (Dt. 12:3), and the converse is that they will not “blot out” the name of their own God. This applies to when God’s name is written in a permanent form, like on a piece of paper, but not when it is impermanent, like on a website. Some Orthodox websites will point out pages that contain the name so that if readers print out the page they don’t dispose of it casually. For this reason, I simply didn’t put the Hebrew letters on my page at all.

Another way to show respect is to employ a substitute like Adonai (meaning “Lord”) or HaShem, (meaning “the name”). That is the reason that Bible translations traditionally use the word “LORD” whenever the name of God appears in Hebrew.

(2) Here’s a name-related etiquette tip. If you are having a conversation with an observant, orthodox Jew, many will find it quite offensive if you speak God’s name Yahweh or use it in conversation. (There are a few who do not, of course.) It sounds like you have a stunning lack of reverence and ignorance of your relationship with God. It’s like you’re the six-year-old brat Bart Simpson calling his dad “Homer,” and then slapping him on the back, only a thousand times worse.

Personally, I never once called my mother “Laura” even though that was her name. “Mom” expresses our loving relationship better.

Leigh Ann Viche says

Interesting….sometimes hard to realize english is not the language of others….

Vicki Newby says

Thanks for explaining this, Lois. Fascinating! I didn’t realize you didn’t use the Hebrew letters for God’s name until I read the footnote. I’ve been interested in learning the Hebrew alphabet lately. I started with aleph. It’s going to be a slow process. Ha!

Doug Ward says

In the world of mathematicians, the iconic example of multiple transliterations is the name of the Russian mathematician Chebyshev (or Tschebycheff, etc.) There’s a fun little book about this, The Thread by Philip J. Davis, a Jewish mathematician.

Lyn Hetherington says

Thank you, there’s so much to learn. And thank you for your book, “Sitting at the feet of Rabbi Jesus.” Its by my bed and I refer to it often. Now plan and look forward to your latest one.. Thank you again, and God bless,

Shalom,

Lyn

Mary says

This is so fascinating. I love learning from you Lois! For a long time I have wondered why, even in Strong’s, words with a “K” sound are written in English with a “Q”. I’m going, But, but, but in English a Q always gets a U after it. And sounds like kw.

Lois Tverberg says

Mary, the reason “q” is used to represent a “k” sound is because its a transliteration of the Hebrew letter that is pronounced kof or kuf and looks like this: ” ק ” and represents a hard “k” sound. You can see that it looks like a backwards q. When Hebrew speakers are transliterating their words with English letters they have no concern about traditional English grammar rules about always using a “u” with a “q” and then saying “kw.” They aren’t trying to speak English. They are trying to speak Hebrew but use English letters that are rough equivalents.