I recently received a question about Jesus’ words in Matthew 18:20, “For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I among them” which I discussed in my book Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus, page 72.

Many scholars read this line as meaning that Jesus promises to be present when his followers gather to pray in his name (meaning, by his authority, because they are his servants). In Sitting at the Feet, I assumed this interpretation and discussed the importance of gathering in community.

More than one reader has pointed out articles like this one that note that this verse is just a few lines after Jesus’ teaching about going to someone who has sinned against you (Matt. 18:15-20). In verse 16, the “two or three who are gathered” are witnesses who you have brought before the sinner so that he can repent. So they feel that we should read this line as only about making a decision in a determination of guilt, not about the need for community in study and prayer. This sounds logical because of the law in Deuteronomy 19:15 that at least two witnesses must be brought to make a legal decision. This law is cited many times in the New Testament, which I’ve written about elsewhere.1

Striking Rabbinic Parallels

Despite how logical the legal conclusion seems, I still disagree. This is because there are striking parallels to Jesus’ saying in Matthew 18:20 within wider Jewish thought. Several sayings sound quite similar, like…

“When two sit together and words of Torah pass between them, the Divine Presence rests between them” Mishnah Avot 3:3

“When three eat at one table and speak the words of Torah there, it is as though they have eaten from the table of God.” Mishnah Avot 3:4

“Whenever ten are gathered for prayer, there the Shekinah rests.” Talmud Sanhedrin 39 (The “Shekinah” refers to God’s presence made manifest in a glorious way.)

“When three sit as judges, the Shekinah is with them,” Talmud Berachot 6

Note that this last line is about God’s Shekinah being present even when people are judging, reminiscent of Jesus’ words. The other quotations are about Torah study or prayer. These two ideas overlap, actually. Rendering judgment requires a type of Scripture study, because rabbis were often asked to interpret the Torah in order to decide whether it had been broken or not.

There’s also a longer discussion about how many people are required for God’s presence to be among them:

Rabbi Halafta ben Dosa (~100 AD) used to say: ‘If ten men sit together and occupy themselves with the Torah, the Divine Presence rests among them, as it is written (Psalm 82:1) “God has taken his place in the divine council.” And from where do we learn that this applies even to five? Because it is written (Amos 9:6) “And founds his vault upon the earth.” And how do we learn that this applies even to three? Because it is written (Psalm 82:1) “In the midst of the gods he holds judgment.” And from where can it be shown that the same applies even to two? Because it is written (Malachi 3:16) “Then those who revered the Lord spoke with one another. The Lord took note and listened.” And from where even of one? Because it is written (Exodus 20:24) “In every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you.” Mishnah, Avot 3:4-7

I don’t think this discussion was intended to be a hard-edged theological proof about where God is present and where he is not. Rather, it seems to be a sermonic exhortation to study, pray and decide matters of Bible interpretation in the presence of others.

The rabbinic discussion may be related to the fact that ten adults (a minyan) were required for communal prayers to be prayed. The rabbi seems to be saying that this doesn’t necessarily mean that God is only present when ten people come together. It quotes Scriptures that point out many places where humans assembled and God is in their midst.

The common denominator in all of these rabbinic statements is the presence of God being especially near when his people gather to meditate on how he wants them to live. This is really the central point of each line. Sometimes people are praying, but sometimes they are studying or judging a trial.

Jesus’ statement fits right in among them, and it sounds like his words about “two or three are gathered” have a similar intention, stressing the idea of gathering and praying as a group in order to discern his will.

The Verse that Began the Discussion

There is one more reason why I’m convinced that Matthew 18:20 is about gathering for a broader spiritual purpose than to make a decision of innocence or guilt. It’s because of the fact that the wording of Jesus’ saying bears a strong resemblance to a key line in the Torah, Exodus 20:24:

In every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you.

This line comes immediately after the ten commandments, when God subsequently tells them to how set up an altar to worship him. Multiple rabbinic commentaries say that this refers to God’s promise that the Shekinah would come and dwell in the Tabernacle and Temple. (Notice that in the discussion about God’s presence by Rabbi Halafta ben Dosa above, it even ends by citing this critical line.)

Consider how this line compares to Matthew 18:20:

For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I among them.

God promised his presence where ever “his name is remembered,” and Jesus promised to be present whenever people “gather in his name.” By talking about gathering “in his name,” Jesus seems to be deliberately harkening back to this ancient line, but now, people are gathering in Jesus‘ name, rather in the name of the LORD.

God promised his presence where ever “his name is remembered,” and Jesus promised to be present whenever people “gather in his name.” By talking about gathering “in his name,” Jesus seems to be deliberately harkening back to this ancient line, but now, people are gathering in Jesus‘ name, rather in the name of the LORD.

Even though a few lines before he was talking about having two or three witnesses to establish guilt, I would say that he has now has shifted the discussion to being about his presence being near his disciples when they gather, and that he would be listening to their needs and prayers with the intention of responding to them favorably.

A Claim to Identity with God?

It’s fascinating to notice that while the rabbis were talking about God’s presence being near, Jesus was talking about his own presence. This is really quite shocking! The rabbinic quotations above were recorded in Jewish literature after the time of Christ (200 – 500 AD). Because of the hostility between Christians and Jews, it’s very unlikely that later rabbis would have expanded on an audacious statement that Jesus was known to have made.

When you compare Exodus 20:24 to Matt 18:20, it sounds like Jesus was equating his presence with the LORD’s. Christians are used to reading this idea into Jesus’ words so we aren’t overly surprised that he would say this. To his original audience, however, it must have seemed quite galling, far beyond what was appropriate if Jesus was only a wise human teacher.

When you compare Exodus 20:24 to Matt 18:20, it sounds like Jesus was equating his presence with the LORD’s. Christians are used to reading this idea into Jesus’ words so we aren’t overly surprised that he would say this. To his original audience, however, it must have seemed quite galling, far beyond what was appropriate if Jesus was only a wise human teacher.

What’s fascinating is that Jesus’ words become all the more startling when you’re familiar with related rabbinic sayings about the Shekinah, even though they come from a slightly later time.

In the context of wider rabbinic thought, it sounds like Christ was hinting at identity with the God of Israel, and promising to personally reveal God’s will to all who earnestly seek him out.

Another Astounding Claim

Another example of Jesus making a subtle but shocking claim is Luke 6:46-49, in the parable about building a house on a rock:

Everyone who comes to Me and hears My words and acts on them, I will show you whom he is like: he is like a man building a house, who dug deep and laid a foundation on the rock; and when a flood occurred, the torrent burst against that house and could not shake it, because it had been well built. But the one who has heard and has not acted accordingly, is like a man who built a house on the ground without any foundation; and the torrent burst against it and immediately it collapsed, and the ruin of that house was great. (Luke 6:46-49)

There is an almost identical rabbinic version of this parable by Elisha ben Abuyah, who lived just a few decades after Jesus:

Said Elisha ben Abuyah: “A virtuous man who has studied the Law diligently is similar to one who builds a foundation of stones and a superstructure of bricks; though they be inundated, yet they cannot be moved. One who is not virtuous, in spite of having studied the Law, is similar to one who lays stones on a brick foundation: the smallest freshet will overturn the building.” (Avot de Rabbi Natan 24:1-2) 2

While Jesus’ parable tells listeners about the importance of obeying his words, Abuyah’s parable tells listeners to build their lives on the Torah – not just studying it, but virtuously doing what it says. Comparing the two versions reveals another outrageous claim Jesus made – that his teaching was God’s authoritative word! Mark 1:22 reports that “they were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority and not as the scribes.” You can hear how astounding Jesus sounded when you consider rabbinic parallels.

These are only two examples of bold claims that Jesus made in a very Jewish way.3 Only when you hear the wider conversation going on around him do you realize the divine authority he was claiming.

~~~~~

1 I wrote another article that includes a discussion of the commandment in Deuteronomy 19:15 to always have at least two witnesses in a legal trial. It’s called “Understanding the Bible’s Non-Western Logic.” This law comes up many times in the New Testament, but I don’t think that’s what Jesus’ words are about in Matthew 18:20.

2 Interestingly, even though Elisha ben Abuyah was a widely respected teacher early in life, later he became known as a heretic, quite possibly because he joined the early Jewish followers of Jesus. For more see my article A Strong House.

3 I’ve written about several Messianic claims that Jesus made that were so Jewish that many Gentile scholars have missed them and concluded that Jesus never claimed to be anything but a humble moral guide. See my article, Jesus’ Messianic Claims: Very Subtle, Very Jewish.

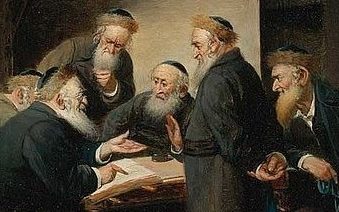

(Photo – Caleb Oquendo, Paintings by Carl Schleicher – Wikipedia)

Carla Gade says

This is so very insightful! I continued to be amazed at Jesu’s teachings as he fulfilled what was said in the law and prophets. Thanks for sharing this great piece.

Rivkah says

Is your conclusion that the Talmudic Rabbis believe in a trinitarian Gd?

Lois Tverberg says

Rivkah, I’m not sure how you concluded this.

The Hebrew Bible talks about the God’s “Spirit” in many places, speaks of God as “Father” and also records God’s promise to David that he would send his own Son to reign over Israel (and also the world.) 2 Samuel 7:14 says, “I will be his father and he will be my son.” The talmudic Rabbis didn’t believe that Jesus was the Messiah, and traditional Judaism doesn’t agree with the Christian idea of knitting Father, Son and Spirit into a Trinity. But the ideas of “Father, “Son,” and “Spirit” come from the Hebrew Scriptures that they do read. It shouldn’t be surprising that the rabbis talked about the “Shekinah” or God’s presence too.

Carolynn Clements says

I so appreciate the way you bring the Eastern, original Hebraic context to life—it helps scripture breathe deeper into my spirit. The key to the cross is dross, and understanding His Word on a deeper level has been a pure blessing.

I’m so grateful for the work you do through En-Gedi Resource Center, your books and Jewish Jewels. Just received the latest edition last night and it made my spirit dance a little jig. Bless you. 💜✝️💜

Martin Allison Booth says

Since my understanding is that through the model of the Trinity everything we do under God is with and for community and ‘The Other’ be that God – Father, Son and Spirit or one another ‘Ubuntu’. In this regard ‘two or three gathered together’ (i.e. in communion with one another and Christ) in order to worship and/or pray makes perfect sense.