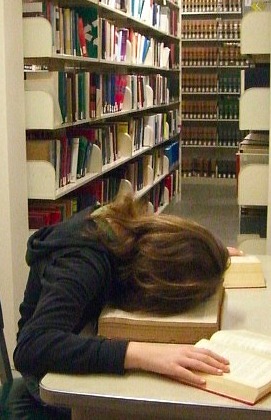

Leviticus is a tough read for modern Christians. We groan at its restrictions and wince at its sacrifices. Many a preacher has used its lines to impress a congregation with how much they should celebrate their freedom from the unbearable Old Testament laws.

Leviticus is a tough read for modern Christians. We groan at its restrictions and wince at its sacrifices. Many a preacher has used its lines to impress a congregation with how much they should celebrate their freedom from the unbearable Old Testament laws.

But what if we turned back the clock to stand beside the Israelites on Mount Sinai? What if we listened to the laws of the Torah through ancient ears?

Many rules that sound strange and distasteful to us wouldn’t have surprised Moses’ first listeners at all. Virtually every culture had food taboos and ritual purity laws. Sacrifices and sacred feasts were commonplace.

There was one difference that would have shocked its first audience, however—God’s ethical laws. Modern readers hardly appreciate the profound difference between Torah and other codes of its time, and how fundamental its precepts are to our own laws.

The Torah’s fairness and concern for all humanity was revolutionary. Other codes had no ethic of equal treatment in regard to rich and poor, so a crime against a person of a high class carried a much greater punishment than one against a low class person. Cheating a nobleman in a business transaction carried the death penalty. But murdering a peasant was punishable by a fine based on his social status. In Israel, however, all were alike under the law, and poor and rich treated equally.

In cases of crime, the Torah was far more humane. In other countries, punishments for even minor crimes were often brutal and mutilating, and often including floggings, amputation and torture. In the Torah, fines were common but physical punishments were rare, and only for severe offenses against the nation or God.

In cases of crime, the Torah was far more humane. In other countries, punishments for even minor crimes were often brutal and mutilating, and often including floggings, amputation and torture. In the Torah, fines were common but physical punishments were rare, and only for severe offenses against the nation or God.

The law that sounds most shocking, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is actually misunderstood. The expression was actually an idiom that wasn’t taken literally, which meant equitable punishment that fits the crime. (An eye for an eye—not a scolding for an eye, or a life for an eye.) It was an ancient expression which intended to limit punishment to no more than the injury itself, because without it, the victim’s clan would exact greater vengeance, escalating into feuds. Scholars believe that it was not followed literally in Israel, but monetary fines were given for injuries instead.

Other legal codes did little to shield society’s outcasts from exploitation. Rather, their main purpose was to protect the assets of the wealthy from the lower class by threatening them with punishment for theft or destruction of property.

Other legal codes did little to shield society’s outcasts from exploitation. Rather, their main purpose was to protect the assets of the wealthy from the lower class by threatening them with punishment for theft or destruction of property.

In contrast, Israel’s laws were uniquely concerned for the protection of the poor, the alien, the widows and orphans. People were to tithe their money to give to the poor, and let them glean from their crops (Dt. 18:29, Lev. 23:22). They were not to mistreat an alien, but to “love them as themselves” (Lev. 19:34). Much of the code of Israel is specifically written to protect the weakest members of the society, unlike any other nation of the time.

The most striking difference was in the laws regulating slavery, which was an accepted part of life in the ancient world. Many of the Torah’s regulations were unheard of in any other culture, and ultimately aimed to undermine the practice altogether. Only six days a week could a master demand a slave to serve him (Dt. 5:14). If a slave was permanently injured by his owner, he gained his freedom (Ex 21:27). If the slave was a Hebrew, he had to be freed in six years and given a substantial gift (Dt. 15:14). Most amazingly, if a slave ran away from his master, he was not to be returned, but allowed to live free anywhere in Israel (Dt 23:15). In every other law code (including even pre-Civil War America), the penalty for not returning a slave was death.

With these differences in mind, the laws of the Torah show great fairness toward all levels of society, compassion for the vulnerable, and amazing concern for the sanctity of human life. Our own culture has been so transformed by these basic principles that we can hardly imagine the world without them.

With these differences in mind, the laws of the Torah show great fairness toward all levels of society, compassion for the vulnerable, and amazing concern for the sanctity of human life. Our own culture has been so transformed by these basic principles that we can hardly imagine the world without them.

The more we see the contrast between God’s ways and the rest of the ancient world, the more we see that the love of Christ in the gospels was fully present in the God who revealed himself on Sinai. We see the Father and Son as one and the same. The God of Israel cared deeply for humanity, and those who worshiped him were to mirror his love and concern as well.

~~~

Further reading:

Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus (Spangler & Tverberg, Zondervan 2009), “Touching the Rabbi’s Fringe” and “Jesus and the Torah” (chapters 11-12, p 145-79).

Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel by Nahum Sarna (New York, Shocken, 1996) 158-89

(Images: umjanedoan, anythreewords, Love for the Torah (Theodor Tolby))

Tirza Tee Bur says

CONTEXT!

It makes so much more sense when we realize the context of that time!

Todah!

Chuck Ferrin says

I came to realize this when I read, “Is God a moral monster?” by Paul Copan. A wake-up for sure.

Jessica P says

One group that seems to be noticeably excluded from this humane treatment prescribed by the Torah is women. My understanding is that women were treated like property under the Old Testament laws. Can you shed any light on this? Thanks so much.