(Based on an excerpt from my upcoming book, Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus (Baker, 2018).

International communications trainer Sarah Lanier has traveled the globe to teach about cultural differences. In her book Foreign to Familiar, she tells about how she handled some Arab boys who were taunting her with catcalls on the street one day. To their surprise, she turned and addressed them in Arabic, asking their names.

Startled, the boys identified themselves, wondering why she wanted to know. Because, she would tell their fathers about their behavior, and how they were being an embarrassment to their families. Horrified, the boys apologized profusely and pleaded with her not to do such a thing.1

Lanier asked the boys their names because she knew that their family’s public reputation, their “name,” was of critical importance in their society. Knowing this helps us decode a much misunderstood word in our Bibles, the Hebrew word shem, which overlaps with the English word “name” but is actually much broader. In older translations we often encounter the word “name” being used in odd ways. Grasping what shem actually means will often help us a lot.

Your Shem is Your Communal Identity

The key to the puzzle of shem is to consider the Bible’s collective context, where a person’s identity within the wider community was of utmost significance. There, the word shem is much more about one’s identity within a community than the verbal label that a person bears, like “George,” “Bill,” or “Mary,” even though the word shem does mean “name” in that sense too.

Imagine that a stranger walks up to you and asks, “What’s your identity?” You could answer by saying “Mary Smith,” but your identity, your shem, is much bigger than that. In our culture, it comes from your education, your job, and how others perceive your status, your reputation, or your authority. To speak “in the name” of someone, biblically, is to speak by his or her authority.

To us, the word “name” usually brings to mind a person’s first name. Notice, though, that the name the Arab boys were far more worried about protecting was their family name. Their family’s shem (in the sense of their identity or reputation) was far more critical than their own.

Here’s a little thought experiment: What does your last name, your family name, say about you? (Think about your family’s reputation, not word origins or nationality.)

If you grew up in a small town where everyone knows everyone and families have been around for generations, it likely tells people a lot about you. Like it or not, your “name” connects you to the people who define you. It reminds people of everything your family has done in the past and forecasts what kind of person you will grow up to be.2

For better or for worse, this little label can have great power. It can be wonderful if you are a Rockefeller or a Kennedy, or terrible if you are a Hitler or a Madoff. This one word can bestow enormous influence upon you or brand you as a reviled outcast, irrespective of anything you’ve ever done in life.

If this is true in our society, just imagine how much more true it would be in a culture where community is everything, where people can’t just leave town to start over with clean slate. How you are viewed by wider society is absolutely critical to your identity as a person. Your name precedes you . . . everywhere.

If this is true in our society, just imagine how much more true it would be in a culture where community is everything, where people can’t just leave town to start over with clean slate. How you are viewed by wider society is absolutely critical to your identity as a person. Your name precedes you . . . everywhere.

When you read the word “name” being used in an odd way in the Bible, you are likely encountering the word shem in its communal context, where honor and shame are everything. To have a “great name” is be well-known and influential, and to have a “bad name” is to be an embarrassment to everyone who knows you. This is why the word shem sometimes doesn’t even make sense translated as “name,” and is better understood as fame, renown, reputation, authority, or honor. See how this clarifies these verses:

Zephaniah 3:20

| I will make you a name and a praise among all people of the earth (KJV). | I will make you renowned and praised among all the peoples of the earth (ESV). |

Joshua 9:9

| From a very distant country your servants have come, because of the name of the Lord your God. (ESV) | Your servants have come from a very distant country, because of the fame of the Lord your God. (NIV) |

Nehemiah 6:13

| …So they could give me a bad name in order to taunt me. (ESV) | …To provide them a scandal with which to reproach me. (JPS) |

Isaiah 55:13

| Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree…and it shall be to the Lord for a name, for an everlasting sign that shall not be cut off. (KJV) | Instead of the thornbush will grow the juniper…This will be for the Lord’s renown, for an everlasting sign, that will endure forever. (NIV) |

The Promise of a New Name

In collective, hierarchical cultures, one’s “name” is closely associated with honor and authority. When the Scriptures talk about God giving a person a new name, it denotes that they are being given a new status in society. Abram, a withered-up wanderer, becomes Abraham, father-of-nations! Sarai, a barren old matron, becomes Sarah, mother of princes! God changed their identity and gave them a new role in society, and it came with a change in name.

In a collective society, rejecting your family heritage will cost you dearly and even cause you to be expelled from your community. Years ago, I was enjoying a lovely dinner with Christian friends who lived in Jerusalem. Another guest they had invited was active in their congregation, and he looked obviously Jewish. To start a conversation, I tossed out a question: “So…what did your family say when you told them you had become a Christian?”

Foolish me. It was like a bomb had dropped in the room.

After an awkward silence, our hostess delicately changed the subject. Later, she explained that when their friend told his parents about his faith in Christ, his father “sat shiva,” meaning that he observed the seven days of mourning at a person’s death. This has been the response of Jews down through the centuries because of the enormous persecution they’ve undergone at the hands of Christians. Because of his faith, this young man had been disowned by his family.

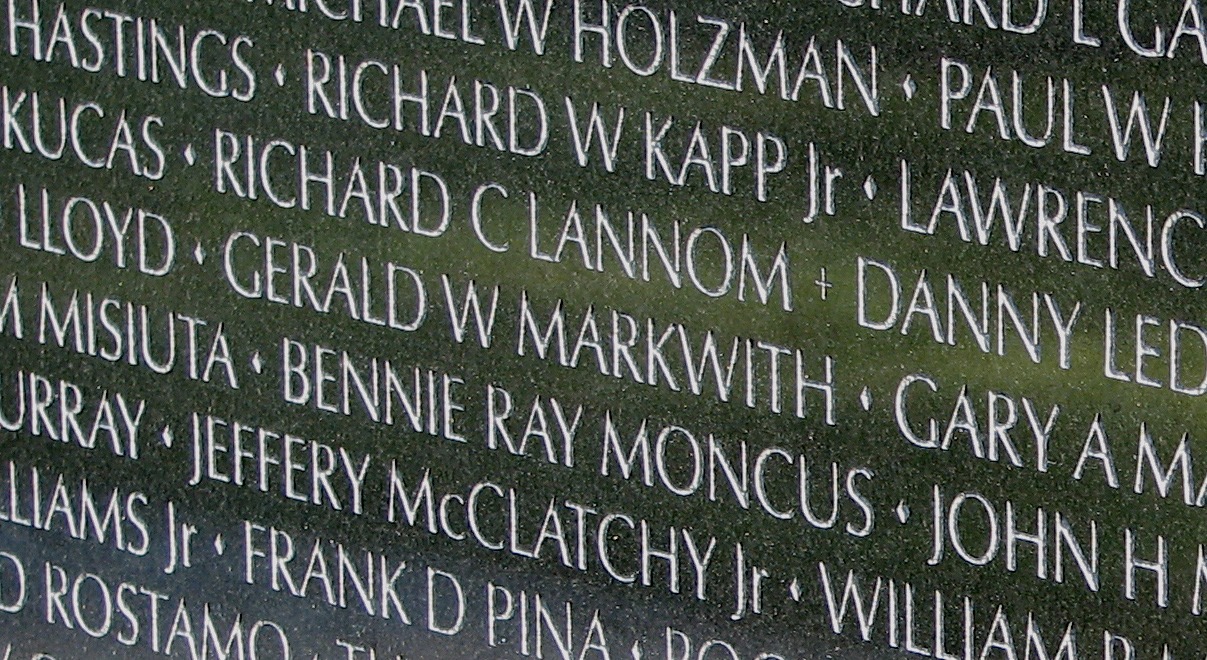

In many cultures, publicly accepting Christ means giving up one’s family, heritage, prestige, and any chance of success in life. This is why Christ promises to give a “new name” to his followers who refuse to deny him in the face of persecution (Rev. 2:17). In this world they may have forfeited their “name,” their reputation, for his sake. But when he comes to reign in glory, these are the people whom he will single out for acclaim. No more will they be known as outcasts but as leaders and princes, with renown to replace the shame they bore during their lives.

~~~~~

A related article of mine is How to Hallow the Name of God, which talks about the Jewish ideas of “Kiddush HaShem” (sanctifying God’s name) and “Hillul HaShem” (profaning God’s name), both of which refer to God’s reputation.

1 Sarah Lanier, Foreign to Familiar: A Guide to Understanding Hot- and Cold-Climate Cultures (Hagerstown, MD: McDougal Publishing, 2000), 45.

2 Women who take their husband’s name, obviously, give up the reputation of their birth family. But since traditionally they invested themselves in building a new family, that was the name they’d take.

(Images: Brad Holt-Flikr, Wikipedia.)

Gemma Blech says

Great Lois. Thanks. I look forward to the whole book

Elgonda Brunkhorst says

I truly believe in the importance of the name. My parents prayed for a baby, got me, then family pressures wanted family names, but mother said God had a name, gave me my name without realuzung the meaning of El is God, gonda comes from Gideon, means warrior.

So all my life they spoke God’s warrior into me. And i love intercession and praying tge will of heavenly Father into being.

It is sad that in general, many millenials have forgotten or not been taught the importance if a name.

Trusting this book will impact many.

Felipe Fernandez says

Great Insight! Keep doing the good work. Thank you

Bruce Newton says

Lois, there is a very important connection to conversion regarding one’s name. When a gentile becomes a Jew, part of the process involves receiving, as one’s parental Hebrew name, the name of Abraham (as in “Bruce ben Avraham”). Notice that in the Great Commission, we are told to go make disciples, immersing them in(to) the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This is actually a new identification with a new family. When I became a Christian, I became a man with a new name and a new family.

Vincent S says

My name is Vincent it’s Latin for “They who overcome/conquer”

Being the 3rd person plural of “to overcome”

My middle name is Michael “who is like God”

behindthename.com says it’s a a rhetorical question, implying no person is like God. But the Archangel Michael is exactly that.

manny says

Who still believes that the Rockefellers and the Kennedys have good names? Those people are as big or bigger sinners than the average schlub.

Lois Tverberg says

Actually, your comment makes my point. I’m explaining that in the Bible the word “name” often means “identity” and that even now our family name creates an expectation because of the reputation of the family. If you met a little kid on the street who said they were a Kennedy or a Rockefeller, that famous last name has created an expectation for you about who they are. Without knowing anything except for the little kid’s last name, you’ve already determined that he is a big sinner, because the whole family is that way…at least in your opinion.

Martha Elisa Matallana Rodriguez says

Creo que cuando hay una connotación negativa referente un apellido , el convertirse en cristiano le da una nueva perspectiva a ese apellido.

Steven puletiu says

Can you give me more understanding names in the bible days.did they have last name?I didn’t know name is your identity people make it big but I’m sure this is simple way understanding identity. I thought name mean character too.please give me more study on identity.course try to understand identity in Christ & what do you mean by that?… is it the fruit of the spirit or what is Jesus character?

Lois Tverberg says

No one had a last name in biblical times. The custom was gradually adopted in Europe from the Middle Ages on, and became the norm by about 1900. More at this link.

I’ve written quite a few articles about what “name” meant in the Bible. Some are on my other website, like this one:

In the Name of the Lord

How to Hallow the Name of God

One thing to be aware of is that the Hebrew word shem that we translate as “name” actually means more than “verbal label for a person.” It often refers to reputation or authority. When we pray something in the “name of Jesus” we praying by his authority.

I would not say that “name” means character specifically, more likely it says that this is the character you have a reputation of having.

I also wrote a chapter about “name” in my book Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus that you can read.