Many of us are frustrated by why no one seems to be able to come up with one perfect English Bible translation. Why are there so many versions? Why can’t we just have one final, best English translation?

A major reason is because of one aspect of language that most of us don’t appreciate. When you speak, you “paint,” in a sense. You choose from a list of words in your language that have hues and overtones you’re looking for, and you blend them into sentences to express what you mean.

A major reason is because of one aspect of language that most of us don’t appreciate. When you speak, you “paint,” in a sense. You choose from a list of words in your language that have hues and overtones you’re looking for, and you blend them into sentences to express what you mean.

Each language has a palette with a finite amount of colors, which have evolved from the cultural memories and common experience of its users. When you try to “paint” a scene in a different language, the same words can have different shades of meaning, so the result is never exactly the same.

This is especially true between Hebrew and English (and less so with Greek). Hebrew is full of desert browns and burnt umbers of a nomadic, earthy people who trekked through parched deserts and slung stones at their enemies. Overall its palette only contains a small set of colors – about 8000 words, in comparison to the 100,000 or more of English. Because of its small vocabulary, each word has a broader possible meaning.*

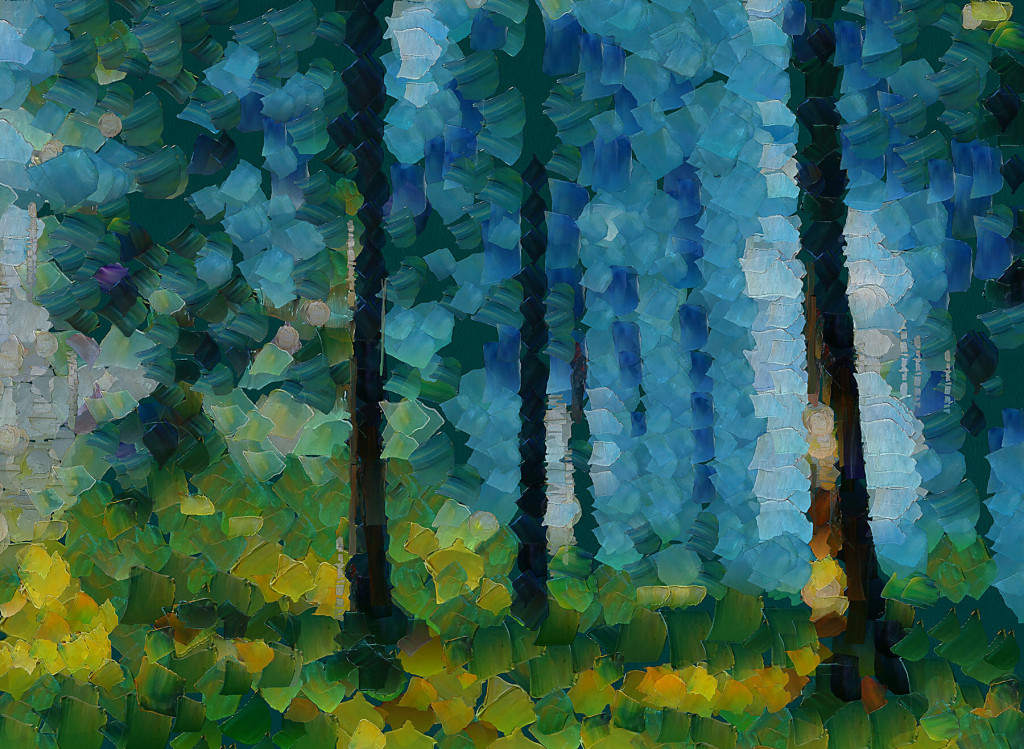

The Hebrew of the Bible paints reality like the picture above. It express truth by splashing on rich colors with a thick brush, like Van Gogh. Notice how even though the details are quite rough, you mentally fill them in, inferring them from the context. Your mind is used to doing this – figuring out meaning from context. Even when you communicate in English, you rely a lot on common experience to fill in the gaps. You sketch out a scene with a few word-strokes, and let people figure out the rest. Hebrew simply relies on this much more than we do. (A lot of languages do this, actually – this isn’t unique to Hebrew.)

Now, imagine yourself as a Bible translator who is “repainting” the image above in English. If you’re trying to translate word-for-word, you can only use one stroke of your brush to portray each stroke in the original. But you have to trade your wide Hebrew “brush” for a fine-tip English “brush,” and you have a different palette of colors. Each of your strokes is slimmer, more refined, and can pick up only one specific shade of the original swath of color.

What will you do?

Most likely, the result of your efforts will show people the overall scene, but it won’t quite capture the atmosphere of the original. If another translator does it, they’ll bring out different nuances. Certainly some renderings will be better than others, and it’s possible to do a bad job. But it simply isn’t possible to perfectly reproduce this painting with a different palette and different brushes.

This is why, when people ask me which translation is best, I tell them that the best thing to do is not to rely on one translation. It’s actually better read from more than one and then compare them. Read a few major translations that try to be more word-for-word (ESV, NASB, KJV, NIV) and then look at some that are less so. Then, start learning more about the original words in Hebrew and Greek, so that you can figure out why Bibles differ. When you see how different artists paint the same words, you start to actually get a sense of the colorful hues of the original.

~~~~~

~~~~~

*I’ve written about this often – about how Hebrew uses the same word for “hear” as for “obey,” and how they use the same word for “fear” as they do “awe” and “reverence.” Greek is more similar to English, so you see this less. See my book, Listening to the Language of the Bible for more. See also my article, “Translation Debates: A Jewish View.“

Another helpful resource came out just recently: One Bible, Many Versions (Intervarsity Press, 2013). The author, Dave Brunn, is a bible translator in Papua New Guinea. He talks about the process of translating and compares several popular Bibles that advertise themselves as “literal” but actually are not in many places, and for justifiable reasons. He uses this to share wisdom with readers about many issues in translation.

Margaret Bosanquet says

Exactly. I often tell my Hebrew students that Hebrew is painting a picture or needs chewing to get the full flavour. That’s part of what makes it so much fun and very rewarding. Even the best Bible translator can achieve only a part of what might be in the text, no matter how hard they work. An informative and important article. Thank you. And I hope it might encourage someone to study Hebrew for themselves.

Melech Adom says

Thank you for your insight. I’ve been reading the Bible for the last 50 years and have always hit my head up against the wall of the various translations/ mis-translations. Having recently joined a Hebrew study group under a dynamic Hebrew language teacher, I have just begun to look over the top of the wall and see a beautiful garden of colour in the Hebrew Scriptures. And when I get to Heaven I will then be able to speak Hebrew even more perfectly.

Melech Adom

Robin Hamar says

I found the English translation that is based on the Hebrew and it gives more specifics and details that the others don’t have but its very heavy.

Its called thenetbible,org

Valerie Martinez says

Thank you for this beautiful picture (pun intended) of Bible translation!

My husband and I are translating the New Testament into his first language, Quiatoni Zapotec, and we are often asked “What version are you translating?” We tell them that we use as many translations as we can get on our hands on!

Thank you for explaining such a basic facet of translation.